Public Speaking

- Introduction

- Why Me?

- My Five Rules for Public Speaking

Since 2021, I have been delivering a yearly class at Lyon1 University on public speaking. The summary of the class is available below.

In this document, I will try to condense the essence of the lecture. That, in turn, is based on my experience as a speaker. To give it structure, I will present my five rules for public speaking; but do not worry, you’ll know I like to break my own rules.

Note: the class includes an exercise based on Cicero, a card deck that helps organize your thoughts for presenting. I am not affiliated nor paid by Sefirot, so this is a genuine recommendation. Given that the tool is copyright protected, I will not include here the material we use in class, but just the abstract concepts.

Introduction

Why is public speaking important in academia? The answer lies in the modern research cycle. For simplicity, I distinguish three phases: Vision, Execution, and Dissemination.

-

Vision is about projecting your research ideas into the future. Try to guess how the scientific world will unfold and what ideas will succeed. Developing a vision is a maturity step in a researcher’s career. Many people have spoken about it, so I will just refer you to their words. I believe we should try to have a vision as soon as we feel confident about it. However, this is a step that typically occurs later in a researcher’s career path.

-

Execution is the technical part of research. For computer scientists, this includes coding, experiment design, statistical analysis, but also technical writing. Execution is, in my experience, where most of us start. Indeed, we borrow our initial ideas from our supervisors, who guide us in transforming them into an action plan. Students with a good technical background excel in the execution given their deep understanding of technology and the principles behind them.

-

Dissemination is about telling others what you did. In my experience, this is the first obstacle in the work of a student with a strong technical background. Mostly because they face two challenges: (1) they are not used to speak about something to someone who has no idea what they are talking about, and (2) they are not used to avoid unnecessary details and distill the essence of their work. In my career, I encountered several types of dissemination activities, but they can all be clustered into three main groups:

- Papers: long, curated, technical essays about the work, that aim at easing scientific validation

- Presentations: medium-long lectures (30 min or more) about a topic, that aim at one or more pedagogical objectives

- Pitches: short encounters with or without visual support that aim at being persuasive.

This lecture is about Presentations, but some of its goals can be passed for the other two.

Why Me?

I love speaking in public! I have sometimes defined the stage as “my safe place”. I consider myself a decent speaker. At least based on colleagues’ feedback.

You may ask, how did you become a decent speaker?

The truth is, back in 2016, I gave my first presentation at ESWC 2016, and… it was terrible. But practice makes perfection. Since then, thanks to my job, I have been giving talks everywhere, a lot. Also, as part of the researcher’s work, is to debate, discuss, etc., etc.

My Five Rules for Public Speaking

The Medium is the Message

Clearly, this is not my invention. This punchline comes from Marshall McLuhan’s seminal book “Understanding Media”. The book focuses on media, not the content that they carry, as the subject of study. McLuhan suggests that each medium affects the audience as much as the content. But what is McLuhan really talking about? Let’s proceed scientifically, and jot down some definitions.

A message is a discrete unit of communication intended by the source for consumption by some recipient or group of recipients.

and

A Medium is an outlet that a sender uses to express meaning to their audience, and it can include written, verbal, or nonverbal elements.

McLuhan highlights that a given unit of communication is biased by the outlet we use to share it. Let’s dig into it by examples.

Let’s say you want to break up with your partner. You choose these exact words, “I need to move on because I do not love you anymore”. You can share these words using any of the following mediums:

- You write a letter, and you slip it under their door.

- You meet them, and you talk to them.

- You call them, and you talk to them.

- You send them a vocal message.

- You send them a written message.

What is the difference?

It is important not to fall into communication nihilism and to think “if communication is always biased, why do we even bother?” Indeed, your audience needs you. Your job is not to aim for unbiased communication but, while conscientiously avoiding logical fallacies, share your take on the topic.

McLuhan again, distinguishes between media such as print, photographs, radio, and movies that are said to be hot media, and media such as speech, cartoons, the telephone, and television that are considered cool media.

Hot media are ‘high definition’ because they are rich in sensory data. Cool media are ‘low definition’ because they provide less sensory data and consequently demand more participation or ‘completion’ by the audience (a useful mnemonic is to imagine that hot media are too hot to touch). Reference.

A clarification from wikipedia: Film, for example, is defined as a hot medium, since in the context of a dark movie theater, the viewer is completely captivated, and one primary sense—visual—is filled in high definition. In contrast, television is a cool medium, since many other things may be going on and the viewer has to integrate all of the sounds and sights in the context.

Critics of McLuhan’s idea contend that the level of audience involvement is not primarily determined by the medium alone, although its capabilities may have some influence. Instead, they argue that audience engagement depends more on the content being presented and how the medium is utilized in particular situations and contexts.

How can we use this information?

Speech is considered (by McLuhan) a cold medium, because it involves multiple senses with low definition and, thus, it demands the audience participation.

- The role of the presenter is “Warming it Up”;

- Predicting the questions;

- Echoing each main point multiple times.

The role of Narrative

The need for a Method

You need a Jargon

As paradoxial as it sounds, it is up to you to define the language of your talk. This is not completely free choice, it highly depends on who your audience is. Nevertheless, there are some foundamental rules that we can recall in order to set up our language.

Terminology

On Synonyms: truth is that they do not exist

“The dictionary is based on the hypothesis — obviously an unproven one — that languages are made up of equivalent synonyms.” – Jorge Luis Borges

Syntax => Semantics (reads, syntax implies semantics)

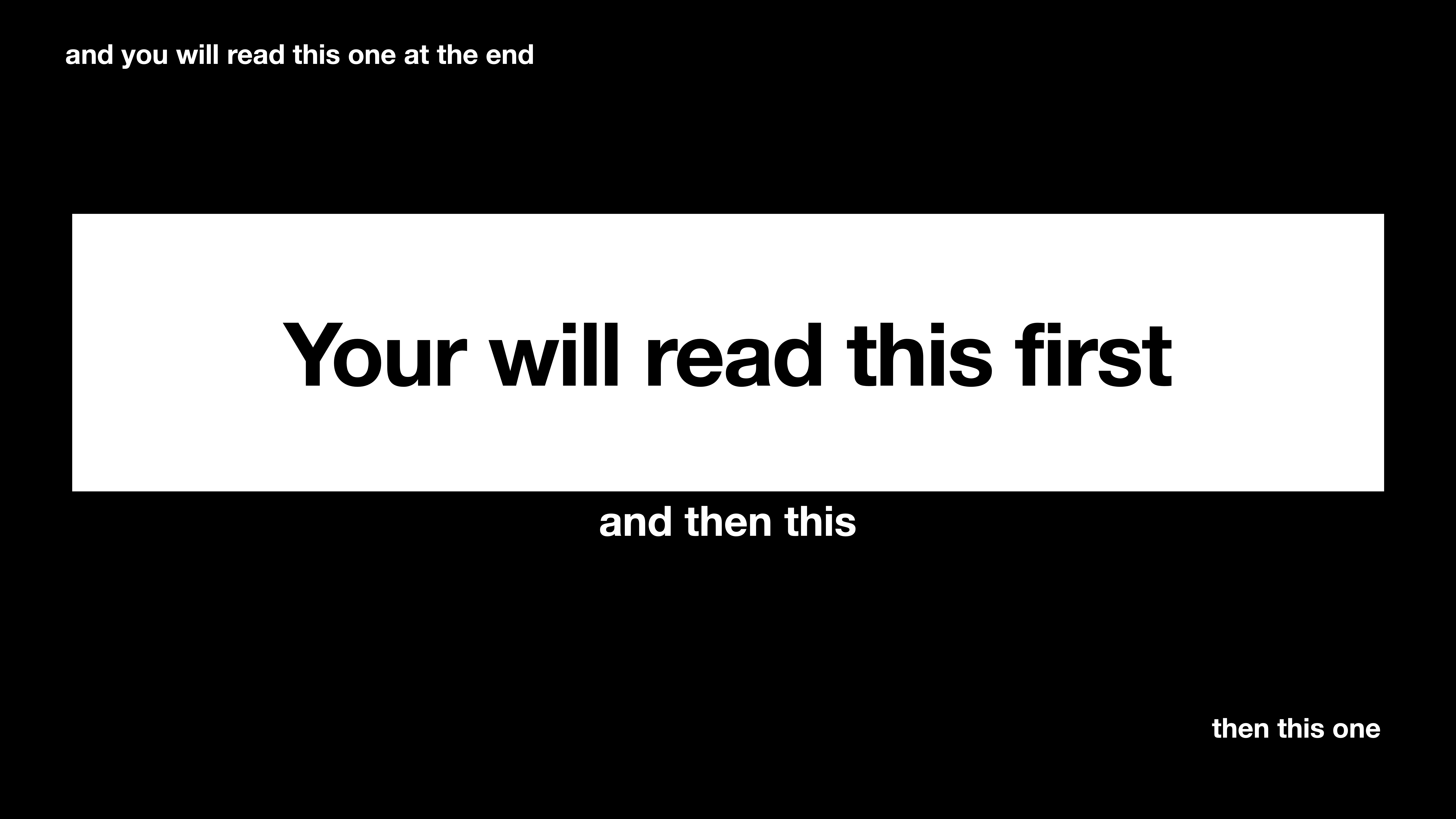

Formatting: Important vs Non-Important

Titles

On Highlighting

Bad

The structure of *scientific* inquiry often relies on a system of principles and rules known as a scaffold. This framework serves as a blueprint, guiding researchers towards the acquisition of knowledge in a systematic and organized manner.

Good

The process of scientific inquiry is often based on a set of principles and guidelines known as a framework. This framework provides a plan for researchers to gain knowledge in a systematic and organized way.

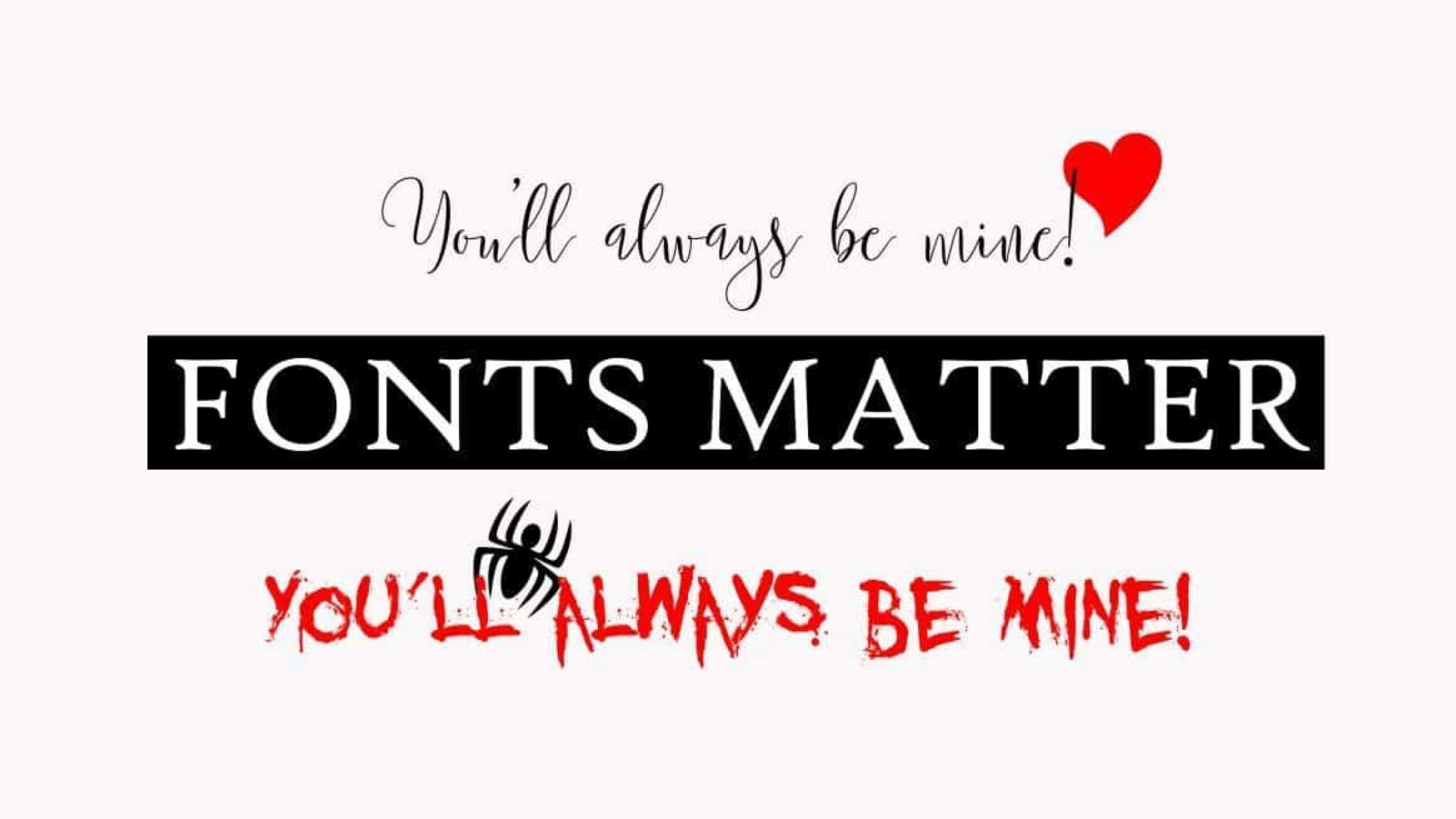

Fonts: why they matter

Have Fun!

Nobody wants to lisstens to someone who does not want to talk in the first place.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: